Why Motivation Fails Without Systems (And What Actually Helps)

Science Translated

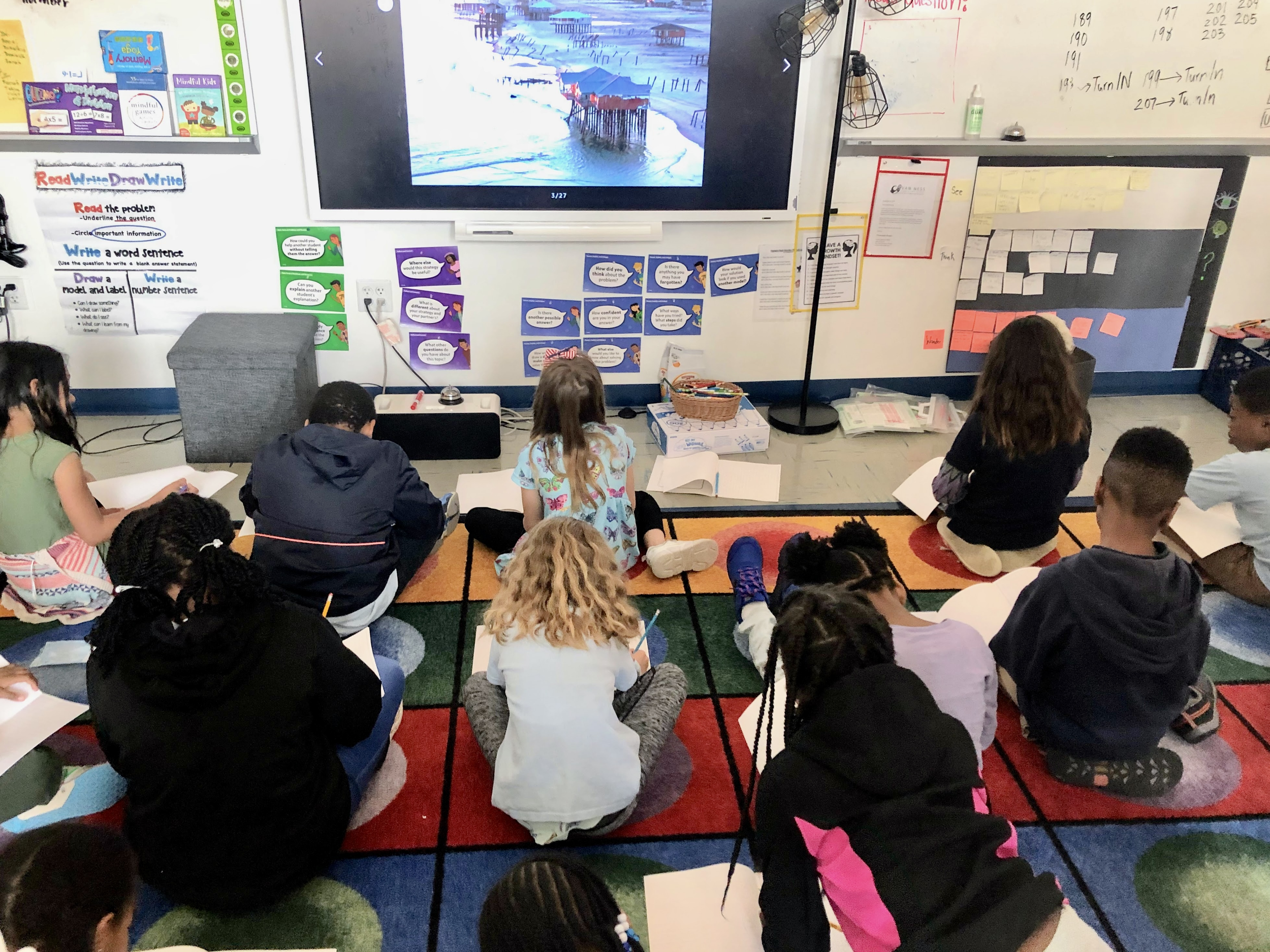

At the beginning of a school year—or a new semester—

you can almost feel the motivation in the room.

Students arrive ready. Parents are hopeful. Supplies are fresh. Intentions are high.

And then, not very far in, something familiar happens.

A student gets frustrated. A concept doesn’t land as quickly as expected. Progress feels slower than it should be. Motivation drops—not because the student doesn’t care, but because effort isn’t producing the kind of results they were anticipating.

This is usually where people reach for the wrong explanation.

They assume the problem is motivation.

The Misdiagnosis

When learning stalls, we often tell ourselves—or our kids—some version of the same story:

If you were more motivated, this wouldn’t be so hard.

But in practice, motivation rarely disappears on its own. It collapses when the conditions around learning aren’t doing their job.

In classrooms, I’ve seen students try to jump ahead to the “point” of a lesson without spending time in the process of understanding it. They want the answer, the outcome, the proof that they’re doing it right. What gets skipped is the slower work: asking questions, making mistakes, receiving feedback, and trying again.

That isn’t a character flaw. It’s a systems issue.

What Learning Actually Requires

Research on learning and behavior has been clear for a long time: progress depends far more on how learning is structured than on how motivated someone feels at the start.

Two ideas are especially relevant here.

Executive functioning refers to the mental skills that help us plan, focus, remember instructions, and manage frustration. These skills are still developing in children—and they fluctuate in adults, especially under stress. When tasks move too quickly or expectations pile up, executive functioning gets overloaded. What looks like disengagement is often cognitive fatigue.

Habit formation research shows something similar. New behaviors don’t stick because someone wants them badly enough. They stick when repetition, feedback, and predictability are built into the environment. Intensity might spark interest, but consistency is what carries things forward.

In both cases, speed works against us. Learning needs space to settle.

If you’re curious to read more, organizations like the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University and researchers writing about habit formation have translated this work accessibly for families and educators.

Where Things Break Down

The challenge is that many students—and many parents—haven’t been socialized to value slow learning.

Across schools and adult life, we tend to reward:

Finishing quickly

Getting the right answer

Moving on

What gets less attention is metacognition—the ability to think about how learning is happening—and the feedback loops between learner and teacher that actually make understanding durable.

So when progress feels uneven, people assume something is wrong with the learner.

Students internalize this quickly. Adults do too.

“I’m not good at this.”

“My kid just isn’t motivated.”

“I can’t seem to stick with anything.”

These stories are convincing—and usually incorrect.

What Actually Helps

When learning environments slow down, motivation tends to stabilize on its own.

That doesn’t mean lowering expectations. It means sequencing effort so that understanding has time to form.

In educational settings, this looks like:

Allowing questions to lead instruction

Using feedback as part of the learning loop, not an evaluation at the end

Letting mastery build gradually

At home, it looks similar. Fewer demands at once. Clear routines. Predictable rhythms. Support that reduces cognitive load instead of adding to it.

This is why blaming motivation misses the point. Motivation isn’t the engine—it’s the signal. When systems are aligned, motivation has something to attach to.

Why This Matters for Families

Parents often worry that their children aren’t motivated enough. Adults worry about the same thing in themselves.

But learning—whether academic, professional, or personal—was never meant to rely on willpower alone.

When people are given time, structure, and feedback, engagement becomes more stable. Confidence follows understanding, not the other way around.

The question isn’t whether someone wants to learn.

It’s whether the environment is designed to support learning at the pace it actually requires.

A Question to Sit With

As you think about learning in your home or your own life, consider this:

Where might slowing the process support deeper understanding right now?

Not as a delay—but as a design choice.